by Elizabeth

Missionary culture is very transient. People are always arriving; people are always departing. Arrivals and departures are never on the same schedule. The fluidity and inconsistency of this relational landscape reminds me of the military culture in which I grew up. And although I “knew,” coming in, about the mobile nature of expat workers, I am still surprised by what it does to me on the inside.

I’ve only been in this country one year. In that time I’ve met plenty of people who moved here after me. I’ve met other people to whom I’ve already had to say goodbye. People I had just barely started to get to know. People I had started to pour my heart into. People with whom I had hoped to build a relationship. Poof! And one day, they’re gone.

And that’s only in one year. I dread this happening to me over and over again, for years on end. I say this because I do not like Goodbyes.

And in addition to my excessive fears and worries, my dislike of Goodbyes was actually one of the reasons I didn’t want to move to Cambodia. I didn’t want to MOVE, period. Growing up, I moved a lot. Moves (nearly) always entailed traumatic Goodbyes, and they always entailed traumatic Hellos. So now I just like to stay in one place. After we moved to the Parsonage in 2006, I told Jonathan, “I am never moving again!” That didn’t exactly pan out for me.

Leaving America — and the Parsonage — in January 2012

I lost a best friend once, during an Army move. I didn’t have another best friend for three years. And for reasons totally unrelated to being a TCK, reasons I’m still not quite sure I understand, I eventually lost that best friend too. The loss shook my world – a double whammy in the middle of my Year of Anorexia. (More on that in a future post.)

When I was heartbroken over this friend — and I mean heartbroken — my parents assured me that high school friends generally aren’t lifelong friends, but college friends can be. I must have internalized that pretty well, because I didn’t have another best friend until college, five long years later. It was then that I was finally able to form a lasting female friendship. (Hooray! We’re still friends.) When she got married and moved away, my new husband learned just how unexpectedly unstable I can be when faced with a Goodbye.

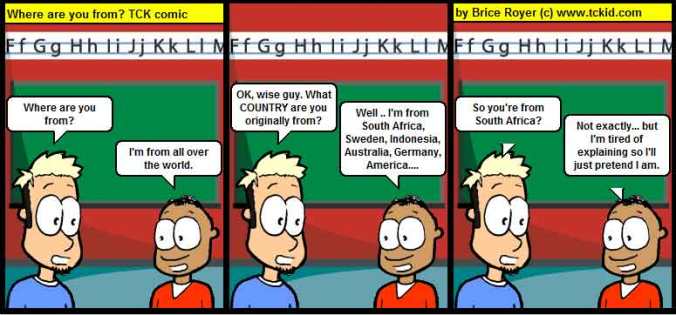

During some of our missions training, an adult TCK shared that there was such a revolving door of people in his childhood that he eventually closed his heart to new people. He just flipped a switch, and turned it off.

I have not yet closed my heart to new people . . . because I really like people. But when you really like people, saying Goodbye is something you really don’t like. And in this transient missionary community, no Goodbye is ever your Last.

I have a remedy for Goodbyes. It includes copious crying and hugging and hand waving. There is a prescription for Getting Lost in Jane Austen. On occasion a secondary prescription for Anne of Avonlea or Jane Eyre might be filled (as there is a Hierarchy of Needs which takes into account the depth of sorrow, time available for mourning, and whether or not the husband is out of town).

You may have a more effective remedy for Goodbyes; this is mine.

Implementing our “I’ll be waving as you drive away” philosophy.

For all of us, though, friendships are seasonal. And as we edge ever closer to the date of our death, we must all say more Goodbyes than Hellos. For military and missionary wives, and their husbands and third culture kids, those Goodbyes are simply accelerated and multiplied. In other words, we bid farewell early and often.

The task of the human heart, then, should any of us choose to accept it, is to open ourselves fully to new people, with the certainty that we will, at some time in this earthly life, have to say Goodbye.

Growing up, this quote from Bernard Cooke was always hanging on the walls of my many homes.

Growing up, this quote from Bernard Cooke was always hanging on the walls of my many homes.