by Jonathan

I love the church, and I have loved the church for a long time.

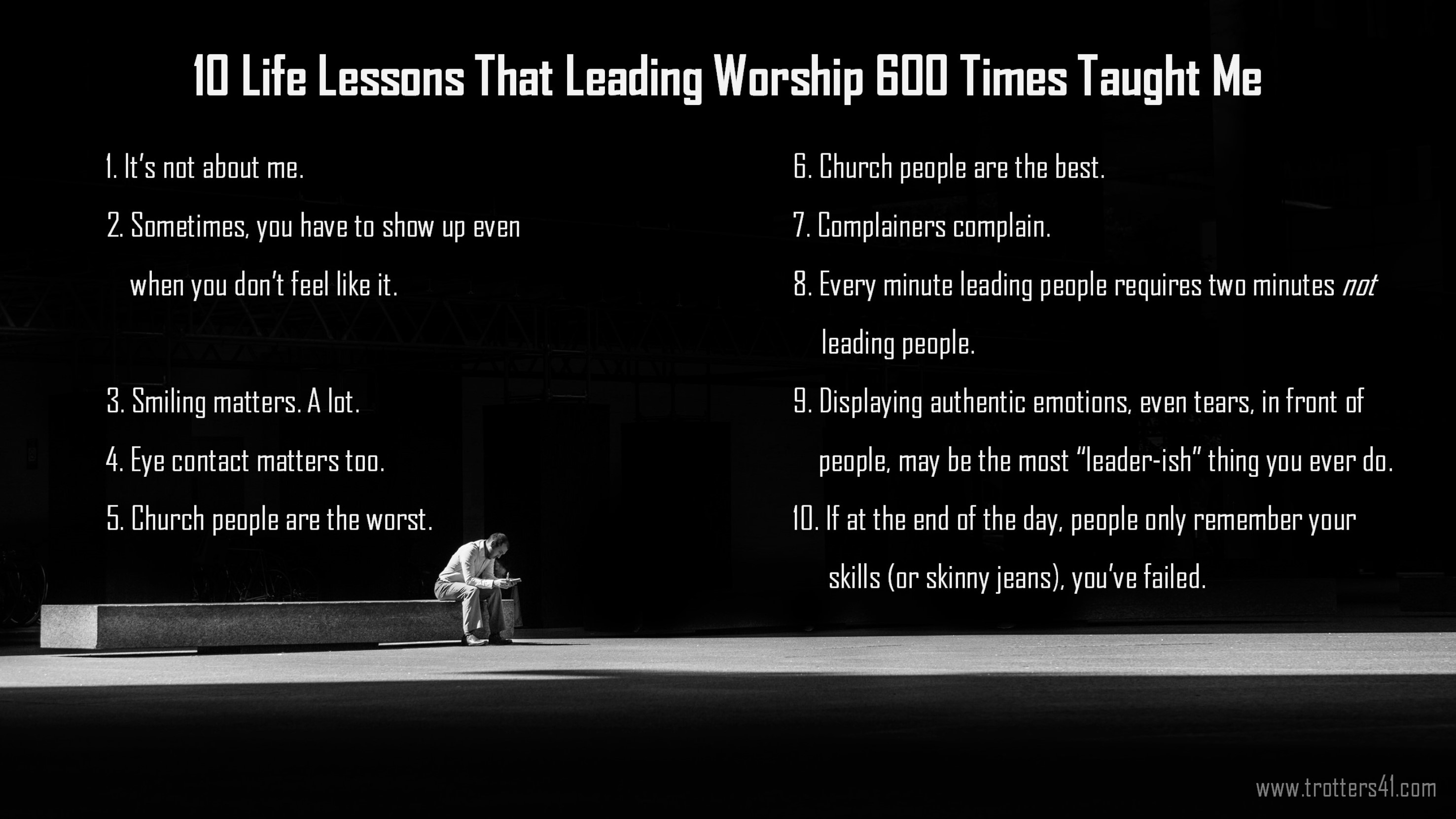

I’ve led worship 600+ times in local congregations. I’ve preached dozens of times across several countries. I served as an overseas missionary in Southeast Asia for 8 years. I’ve been in “church work” in one capacity or another for over 20 years.

In fact, I still serve with a church planting mission organization, providing pastoral care and coaching to missionaries around the world. My day job is walking alongside of hurting people who also love (and are serving) the global church.

I still love the church, but I’ve got a problem.

Watching the American evangelical church for the last several years has been devastatingly hard. Initially, I watched as a sort of outsider, living and ministering in a developing country that had a proud and boisterous autocrat as a leader. And now since COVID led to an early repatriation in March of 2020, I’ve watched from a more comfortable spot in the rural Midwest.

Has it been devastating for you too? Have you grieved at how some elements of the American church have responded to racial issues, to politics, to the Capitol siege, to the ongoing global pandemic that’s killed over 660,000 people in our country alone? Have you lost friends and maybe even family?

During all of this, I’ve desperately wanted to change the church. I’ve shared articles and written Facebook posts trying to convince people to behave differently, to care differently, to love differently.

I’ve needed the church to behave differently so that I would be ok, so that I wouldn’t be embarrassed, or ashamed, or angry. As it turns out, that’s not very loving or healthy.

I’m beginning to realize that there’s a difference between loving the church and being enmeshed with it. There’s a difference between being grieved at her sins and being so emotionally devastated by her sins that I want to scream at people. One is healthy and vital, while the other is evidence of codependency.

Definitions & Caveats

Codependency is “excessive emotional or psychological reliance on a partner, typically one who requires support on account of an illness or addiction.”[1]

In unhealthy systems like this, talking about things openly and honestly can get complicated; silence is of paramount importance, and silence helps to maintain the status quo. One writer described it this way:

“One fairly common denominator seemed to be the unwritten, silent rules that usually develop in the immediate family and set the pace for relationships. These rules prohibit discussion about problems.”[2]

I have felt this. I have felt the urge to sit down, to shut up, to stay silent. But I can’t anymore.

The real-world impact of codependency is complex, but at least in part, a codependent person will seek to control the ill person (or addict) so that the codependent will remain psychologically intact.

This was me. And it’s made me bone-weary.

My identity was so wrapped up in the church that a threat to the church (even if it was from inside the church) felt like a direct threat to my core self. I don’t want to live that way anymore.

Is the American church a functioning alcoholic, drunk on power and patriarchy? Yes, some of it is. But “the church” is a pretty large entity to lump together in an accusation like that. So please hear me when I say this: there are parts of the American evangelical church that really are sick. Those parts need to be honestly assessed and truthfully addressed. But that doesn’t mean it all needs to be burned to the ground.

Eugene Peterson spoke plainly about the tensions of living in (and serving) a community of believers. It was not all rosy. But even while admitting the challenges, he wrote, “I have little time for the anti-church crowd who seem snobbish and who have little sense of the lived way of soul and Christ.”[3]

C.S. Lewis would have agreed, I think. A generation before Peterson, Lewis wrote this in a letter to a friend: “The New Testament does not envisage solitary religion. Some (like you – and me) find it more natural to approach God in solitude; but we must go to Church as well.”[4]

I can’t “do faith” on my own. I’ve gained so much from my involvement in local churches. It has been good for me, spiritually, emotionally, and even psychologically. My family has found a local body of believers in our new town in the Midwest, and we are jumping in to community and fellowship.

I am not anti-church, but I am anti-pretend, and I can’t act like things are OK in the American church.

I resonate deeply with Beattie when she writes, “[C]odependency is called a disease because it is progressive. As the people around us become sicker, we may begin to react more intensely.”[5]

Is that what’s happening to me? To us? Have we been in a codependent relationship with the church? Is this why now, as her behavior appears to become sicker and sicker, so many of us are reacting more and more intensely, getting either angrier or else just running away? I think so.

Churches Love Codependents

Codependents make great church members. They’re sacrificial. They’ll do anything. They’ll go anywhere. And they’ll defend the leaders and the system if they have to. They care a LOT about the church.

Many church-growth strategies look like a playbook for making people codependent. Encourage strong identification with a specific church/leader/group. Call it branding. Teach a lot about the uniqueness of this church and church culture. Create a very strong “us vs. them” motif. Emphasize teachings on authority and respecting spiritual leadership/headship. And if our “family” is ever in crisis, circle the wagons. And God forbid, but if anyone from without or within criticizes the church, take it personally, react vehemently, and DEFEND.

As it does in the world of codependency and addiction, these strategies quickly lead to a persecution complex, and American evangelicals thrive on a persecution complex.

Local Church, Hope of the World?

The now-disgraced pastor and author Bill Hybels used to say regularly, “The local church is the hope of the world.” I used to quote that statement regularly. But you know what? I’ve learned it’s not true. In fact, that message causes a slow but steady trend towards deep dysfunction: Hide flaws. Silence survivors. Conceal abusers (or transfer them somewhere else). Don’t let those on the outside see reality.

Codependents always protect the addict.

But protecting the reputation of the church is a fool’s errand, and it typically ends up meaning, “We need to protect the reputation of our leaders.” If the leader is leading the church that is the hope of the world, or at least the city, then we must protect him, along with the system he leads.

And if a narcissistic politician promises to protect our churches and our “Christian rights,” then we must protect him, too, and hold him above reproach. This is so wrong and harmful for our nation, but we learned it in our churches first.

To put it more bluntly, if the local church is the hope of the world, then the leader of the local church is the hope of the world too. Chuck DeGroat, clinician and pastor, writes about narcissistic church leaders. These leaders are more than happy to be seen as the hope of the world. He writes, “The grandiosity, entitlement, and absence of empathy characteristic of narcissistic personality disorder was translated into the profile of a good leader.” In these systems, “Loyalty to the narcissistic leader and the system’s perpetuation is demanded.”[6]

This is not healthy.

Next Steps

The last few years have revealed some of the addictions and illnesses of the evangelical church: patriarchy, white nationalism, a fervent and enduring embrace of narcissistic, abusive leaders, and a disregard for the truth.

During all of that, we were also taught to love the church. And we did.

I did.

What many of us learned, though, was that we needed to love the church as the prime thing. Nobody said it, but I think we gained more identity from our churches than we did from our Christ.

We desperately need to work on de-centering the church (and politics) and re-centering the Christ, the hope of the world. Karen Swallow Prior recently wrote about this in her article titled, “With this much rot, there’s no choice but to deconstruct.” She says,

“We must make Jesus the head of his bride again. We can no longer put the church — its name, its reputation, its money, its salaries, its staff, its programs, its numbers — before Christ himself.”[7]

Enmeshing ourselves with charismatic Christian (or political) leaders is tempting. It helps us feel like we belong and like we’re on the inside. But if our core identities hinge on our churches or our political parties, we have erred terribly.

The Church Called TOV

This article is not a book review. However, I believe a truthful review of Scot McKnight and Laura Barringer’s book, A Church Called TOV, would be this simple: A Church Called TOV is a textbook for walking out of religious codependency.

It’s that good.

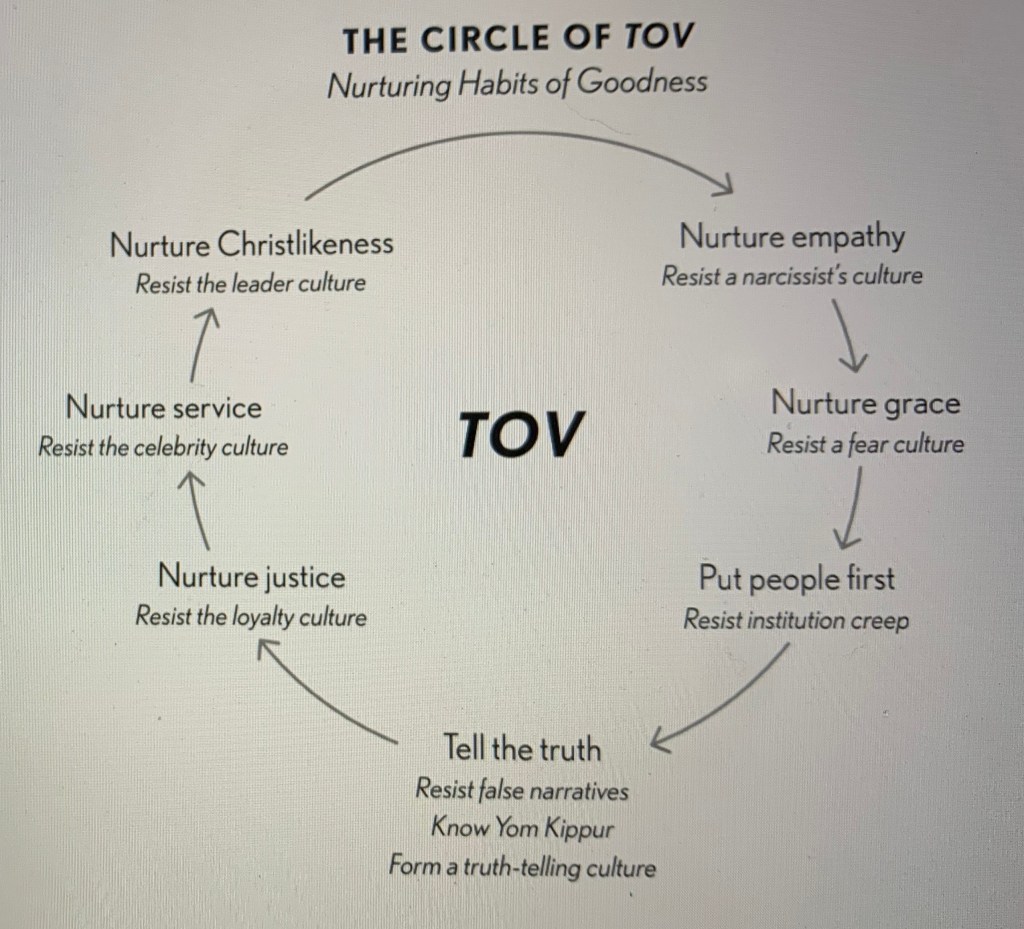

The authors compare unhealthy, dysfunctional dynamics, with gentle, Christ-honoring pathways forward. Here are the main ideas:

Conclusion

I don’t want to love the church in a codependent way anymore. I will still love her, but I don’t want to be enmeshed with her, where her good (or bad) behavior alters my own sense of self.

I want to nurture empathy and grace. I want to put people first and tell the truth. I want to pursue justice and honor humble service. I want to grow into Christlikeness.

I will continue to be a part of my local church, but I don’t want my core identity to come from her. It can’t. I can’t be enmeshed any longer with the American evangelical complex.

The local church (even a great one) is not the hope of the world.

Jesus Christ is the hope of the world.

Amen.

Come, Lord Jesus.

A Lament for the Church: a prayer of letting go

The path to healing from codependency often involves an emotional detaching. That does not mean you care less for the person from whom you’re detaching. It just means you are detaching from “the agony of involvement.”[8]

This lament, patterned after the material in Mark Vroegops’ book, Dark Clouds, Deep Mercy, is my attempt not to care less, but to care healthier.

God of the Church, the one who sees the end from the beginning, hear my cry to you today. You established the heavens above and the Church below, and one day you will invite your Bride, your people, to feast with you in the New City, the golden city of God.

But here and now, O God, your Bride seems sullied. More to the point, your Bride seems to be chasing after the wind, pining away for other lovers who promise power and a seat at the table. Your people are damaging people. They have turned on the least of these, preferring instead to join in with mockers, to stand with sinners.

You will not be mocked, and you will not endure their sins forever. So do something! Stop this madness! Bring light back to our eyes. Make compassion great again! Do not stop your ear to the cry of your people. No! Listen to their fawning over false prophets, see their bowing before every lying hashtag and would-be tyrant. Open their eyes and break their hearts!

You alone know, O God, the depths of the deceit, and the depths of your love. I yield the floor, trusting that this is your case to make, and believing that you will. Your ways are too complex and masterful for me to comprehend, so I yield.

I trust you to figure this out and respond appropriately.

And I rest in your promises to forgive me too.

Amen.

[1] Oxford English Dictionary

[2] Codependent No More, by Melody Beattie

[3] As quoted in the book, A Burning in My Bones, by Winn Collier

[4] The Quotable Lewis, by Martindale and Root

[5] Codependent No More

[6] When Narcissism Comes to Church, by Chuck DeGroat

[7] https://religionnews.com/2021/08/04/with-this-much-rot-theres-no-choice-but-to-deconstruct/

[8] Codependent No More